Bear markets and recessions are not identical, but investor responses should be. Staying the course with multi-factor diversification through bears and recessions is our suggested course of action based on a review of the evidence. This thought capsule is a follow-on to our analysis of recessions and factor performance.

By Andrew L. Berkin, Ph.D., Head of Research, and Geoffrey G. Crumrine, Head of Client Service and Marketing

In the early spring of 2020, investors found themselves in a situation they hadn’t experienced for a decade: Confronting a bear market. Global stock markets tumbled in February and March over concerns about the economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic. The S&P 500 Index, which had reached a high on February 19, ultimately fell more than 33% from its peak until bottoming out on March 23—putting the index well into bear territory.

Subsequent economic stimulus efforts from the U.S. government helped improve investor sentiment and stocks began to recover over the following months. Those gains drove the S&P 500 back to a new record high in late August 2020, signaling the end of the bear market. Despite the apparent short duration of the latest bear, stocks remain volatile and many investors are still wary about the future. However, bull and bear market cycles are to be expected when pursuing a long-term investing strategy. Unfortunately, we can’t predict when bear markets will occur or how long they will last, and we can’t control the external factors that help dictate broad market movements. But we can examine historical data to understand how portfolios have performed during past bear markets.

Following up on our recent analysis of recessions and factor performance, we wanted to take a similar deep dive into the phenomenon of bear markets and the performance of the underlying factors that shape stock returns. Bridgeway’s previous research into past recessions uncovered data that emphasizes the fact that it’s risky to try to time both the economic cycle and the market’s performance. Individual factors don’t move in lockstep during recessions. It’s not surprising, then, that we observe similar patterns in the historical record for factor performance before, during and after bear markets. But just as recessions and bear markets are distinct events, factor performance isn’t identical during each.

A Broad Look at Bear Markets Throughout History

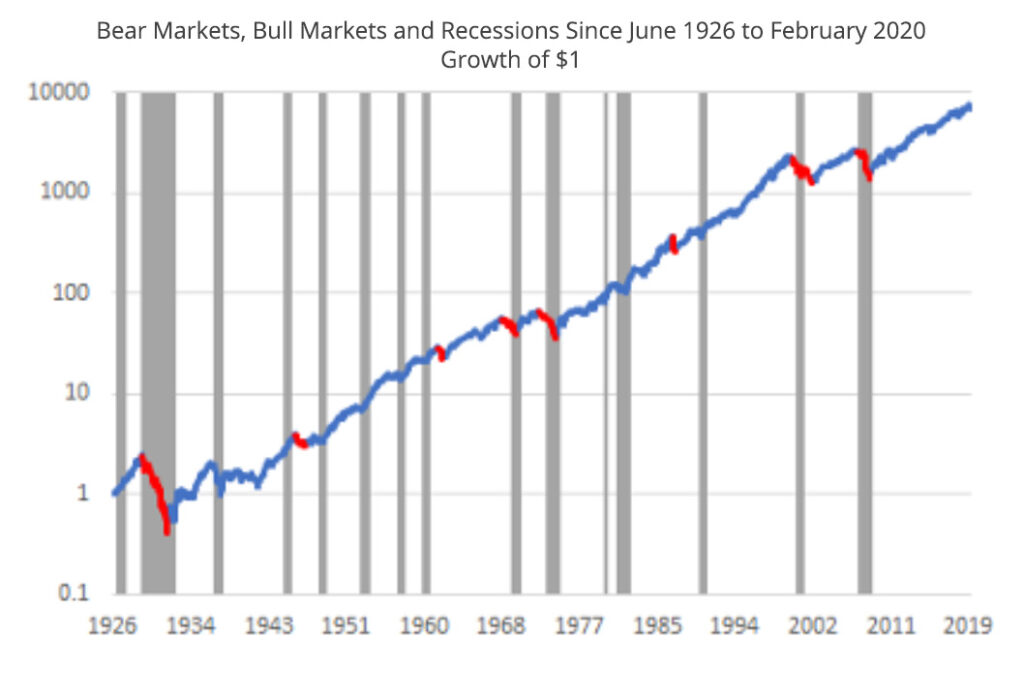

Markets typically are considered to be in bear territory when they have fallen by 20% from their highs. Since 1926 through February 2020, we’ve identified eight bear markets according to this 20% peak-to-trough decline convention (not including the most recent February-March downturn)1.

The chart below illustrates this history. The line shows the growth of $1 invested in the broad stock market, with red sections representing bear markets and blue sections representing bull markets. Overlaid on this graph, we’ve also plotted economic recessions, represented by grey bars.

Sources: Ken French Data Library, NBER, and Bridgeway calculations

First, we note that one dollar invested in the stock market in July of 1926 would have grown to more than $7,500 by the start of 2020. Despite recessions and bear markets, many stocks have been an excellent investment over the long term. In fact, we could replace the word “despite” in the previous sentence with the phrase “because of.” Stocks are a risky investment, but this risk comes with the potential for the higher rates of return that reward investors.

Interestingly, we also see that bear markets and recessions often—but not always—overlap. Since 1926, the market experienced 15 recessions and 8 bear markets. Even when recessions and bear markets coincide, they don’t share exact start and end dates. And sometimes, we have recessions without bear markets or bear markets without recessions. One example is the 1987 bear market, which includes the October 19 market crash often referred to as Black Monday. Although a painful bear market, it did not have a corresponding recession attached.

What are Factors?

Factors are the specific characteristics of stocks and other securities that both drive their returns and explain their performance across different market conditions and business cycles. For further discussion, please see the book “Your Complete Guide to Factor-Based Investing” by Andrew L. Berkin and Larry E. Swedroe.

Factor Performance and Bear Markets

While the data above displays how the overall market has performed since 1926, we also analyzed how individual factors performed before, during, and after bear markets. Table #1, below, shows average factor returns for Fama-French factors and momentum relative to market environment.

Table #1: 8 Bear Markets Going Back to June 1926

Fama-French Plus Momentum Factors, Average Monthly Returns (%)

| Market premium (Mkt-RF) | Small size (SMB) | Value (HML) | Momentum (MOM) | Profitability (RMW) | Conservative investments (CMA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Months | 0.67 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.66 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| Bull Markets | 1.27 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| Bear Markets | -3.70 | -0.34 | 0.76 | 1.64 | 1.10 | 1.32 |

| 12M Pre Bear Mkt | 1.76 | 0.14 | -0.03 | 1.44 | -0.24 | 0.21 |

| 12M After Bear Mkt | 3.25 | 1.02 | 1.16 | -2.06 | -0.24 | 0.26 |

*Average returns through January 2020. Mkt-RF, SMB, and HML data starts in July 1926. Momentum data starts in January 1927, and profitability and investment factors data start in July 1963

Source: Ken French Data Library and Bridgeway calculations

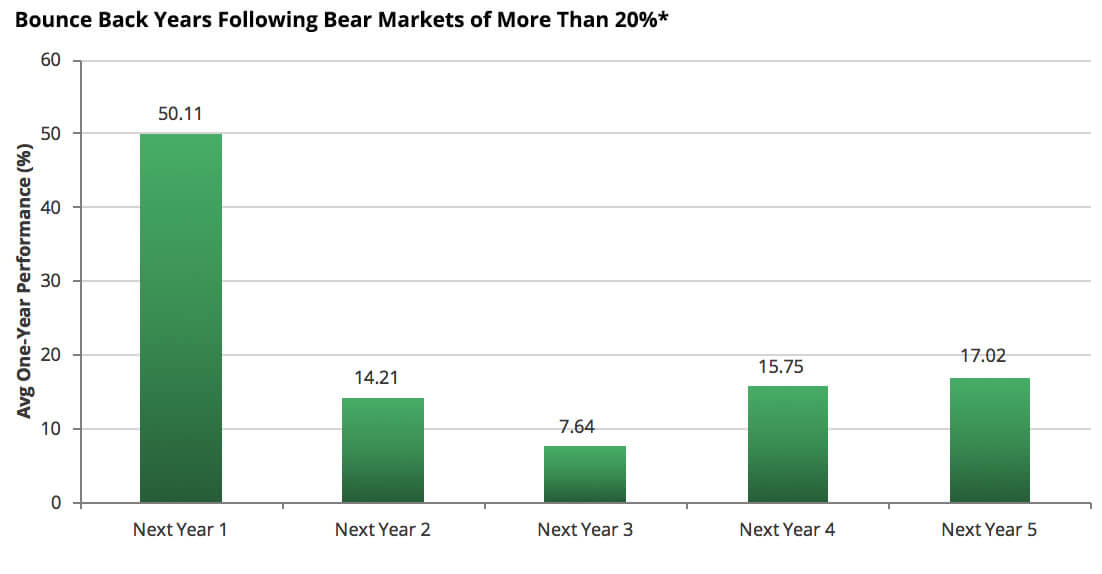

As we see in the second row, all factors did well in the more prevalent bull market months, although the company financial health related metrics of RMW and CMA were weaker than typical. Row three shows that, as expected, the market factor (Mkt-RF) was strongly negative during bear markets but recovered especially well in the 12 months following. Stocks tend to rebound dramatically after a bear market. There is an old saying that no one rings a bell at the top or the bottom of the market. Timing the markets is difficult, and as the recovery from bear markets shows, missing out can be quite costly.

The performance of other factors is quite different depending on the period. Small stocks suffered during the risk-averse times of bear markets but performed strongly in the recovery. In contrast, value stocks held up quite well during bear markets. Noting that value is negative on average in the 12 months beforehand provides some insight into this behavior. The market environment before the onset of a bear is often characterized by exuberance, with growth-led rallies. However, value has come back into favor during the ensuing downturn and subsequent recovery. The aftermath of the late 1990’s technology bubble is a well-known example of this pattern.

Perhaps somewhat surprising is the behavior of momentum, which generally holds up quite well during bear markets but fails miserably afterwards. This pattern was first described by Cooper, Guillen and Hamid.2 When markets bounce back, those stocks that have lost the most often lead the recovery, and momentum suffers. (For more in-depth analysis, see the Bridgeway white paper “When and Why Does Momentum Work – and not Work?” by Andrew L. Berkin.)

When we compare these returns to our previous analysis of factor returns during recessions, we see many similarities—but also important differences. For example, factors related to company financial health (RMW and CMA) perform strongly in both recessions and bear markets, as investors favor higher quality companies in both environments. In fact, the returns for RMW and CMA are even stronger in bear markets than they are in recessions. However, the performance of these two factors diverges in the aftermath of the different events. The profitability factor RMW, which has stronger-than-average returns in the 12 months following recessions, is actually negative in the 12 months after bear markets.

Another difference is the relative effectiveness of the value factor during and after bear markets. Value’s returns are reduced (but still slightly positive) during recessions, and its outperformance in the 12-months following not quite as strong as the substantial turnaround we see following a bear market.

Critically, we see that factors don’t move in lockstep around these two distinct market and economic events. And in both cases, we see dramatic reversals in leading and lagging factors before, during and after both recessions and bear markets. As we said earlier, trying to time these shifts is difficult, which is why we emphasize the importance of maintaining diversification across multiple factors.

Case Study: Bear Market of 2000-2002

Moving down from the 30,000-foot view, let’s examine the bear market of 2000-2002. Previously, we analyzed the recession of 2001 to show that factor performance during that event did not line up with long-term historical averages. For this reason, we thought it would be interesting to look at a bear market that occurred around the same time.

The recession of 2001 started in March and lasted for 8 months, ending in October of the same year. In contrast, the bear market predated the recession (beginning in September 2000) and ran for 25 months (ending in September 2002). It was the second-longest bear market after the one that coincided with the Great Depression.

Table #2: Bear Market of Sept 2000-Sept 2002 (25 months)

Fama-French Plus Momentum Factors, Average Monthly Returns (%)

| Market premium (Mkt-RF) | Small size (SMB) | Value (HML) | Momentum (MOM) | Profitability (RMW) | Conservative investments (CMA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During Bear Market | -2.51 | 0.73 | 2.40 | 1.51 | 3.00 | 1.97 |

| 12 M Pre Bear Mkt | 1.31 | 1.48 | -1.30 | 4.09 | -1.55 | 0.04 |

| 12 M Post Bear Mkt | 1.99 | 1.45 | -0.54 | -2.47 | -1.70 | 1.04 |

Source: Ken French Data Library and Bridgeway calculations

The data for the bear market of 2000-2002 offers a good example of the risks of attempting to time a bear market and tactically adjust factor exposure. While value’s positive performance on average during bear markets hasn’t been as strong as the returns for momentum, profitability, and conservative investments, the bear market of 2000-2002 saw value delivering substantial gains. Recall that growth stocks had been dominant in the tech bubble of the late 1990s and the first quarter of 2000. For the 12 months before this particular bear market, value lagged by an average of 1.30% monthly. The collapse of formerly high-flying growth stocks not only helped usher in the bear market and subsequent recession, but also set the stage for historically discounted and beaten down value stocks to recover strongly. Many investors who had abandoned value stocks during the run-up of tech stocks likely missed out on a substantial portion of value’s gains.

Key Takeaways

As noted earlier, we can’t predict whether a modest drop in stocks presages a dramatic slide into bear market territory. Likewise, we never know if a bounce from market lows will lead to a full recovery or is merely a temporary rally. Examining how factors have performed historically around bear markets is instructive, but also shouldn’t be taken as a prescription for portfolio changes. Remember, the factor returns shown in Table #1 are averages across multiple bear markets, and as we saw when examining the bear market of 2000-2002, they don’t hold every time.

For those reasons, investors should avoid making dramatic changes to their portfolios based on where they believe we are in the market cycle—just as we cautioned against making changes around recessions. Remember that factors have worked over long periods. They don’t always deliver positive returns, but when one is lagging others often provide a positive return cushion. What’s more, those lagging factors have rebounded in the past. For example, small size and value underperformed large growth in the run-up to the most recent bear market and continue to lag. But historical data showing that small size and value have recovered strongly after past bear markets gives us confidence that they will again — we just can’t predict when the turn will happen and how robust the recovery will be.

Considering this evidence, we believe building a well-diversified portfolio with exposure to multiple factors and rebalancing to return to those targets when a factor or asset class moves out of line with your chosen allocation target. That strategy may help investors avoid the costs associated with excessive trading and the substantial risk of missing out on gains by getting the timing wrong as the markets move through their inevitable cycle of bulls and bears.

1 As in our analysis of recessions and factor returns, we have not included the current recession or the 2020 bear market because we have not completed a full market cycle.

DISCLAIMER

The opinions expressed here are exclusively those of Bridgeway Capital Management (“Bridgeway”). Information provided herein is educational in nature and for informational purposes only and should not be considered investment, legal, or tax advice.

Mkt-RF or the equity risk premium is the expected excess return of the market portfolio beyond the risk-free rate. SMB or the size premium measures the additional return investors have historically received by investing in stocks of companies with relatively small market capitalization. HML or the value premium measures the additional return investors have historically received for investing in companies with high book-to-market values. MOM or the momentum premium measures the additional return investors have historically received for investing in companies with positive acceleration in stock price. RMW or the profitability measure is the difference between the returns of firms with robust (high) and weak (low) operating profitability. CMA or the investment factor is the difference between the returns of firms that invest conservatively and firms that invest aggressively.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. Diversification neither assures a profit nor guarantees against loss in a declining market.